ISO When to use a high number.

Want to take photos at night or in a dark place? That’s what high ISO numbers are for. There are times when a low sensitivity setting is the best option, but the fear of creating noisy images makes some photographers avoid high ISO settings like the plague. However, they can be extremely useful and enable some fantastic quality images. To help overcome this fear we’re going to take a look at sensitivity and the situations in which high values are a must.

What is sensitivity?

Digital cameras’ sensors receive light which generates an electric signal that is converted into a digital signal that can be used to create an image. The strength of the electric signal is determined by several factors, including the amount of light that each photoreceptor (pixel) receives. The amount of light that reaches the sensor is controlled by shutter speed and aperture. With film, high sensitivity film requires less light to produce an image than low sensitivity film requires. This makes high sensitivity film a good choice in low light situations and low sensitivity film a good option when there’s lots of light or long exposures can be used. It’s a similar story with digital camera sensors, but as the sensor can’t be changed between shots it has a ‘base sensitivity’ which can be varied by applying ‘gain’ or amplification to the signal. The base value is usually the lowest ‘native’ sensitivity setting that’s available. The downside to applying gain to a signal is that it introduces noise.

What is noise?

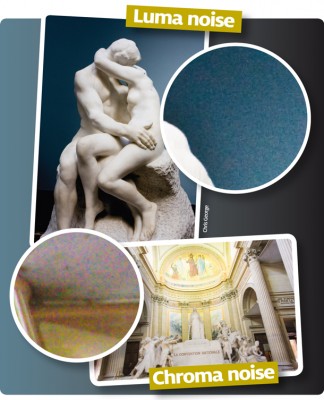

Digital image noise comes in two forms, chroma and luminance. Chroma noise is the coloured speckling that you sometimes see in high sensitivity images, especially in shadows. It can look like individual points of colour or larger patches of colour. Luminance noise occurs where there’s variation in the brightness of pixels that should have the same tone. It looks a bit like the grain of black and white film. Luminance noise is often left behind when chroma noise is removed.

Native and expanded sensitivity

Most interchangeable lens cameras have a ‘native’ or standard sensitivity range that usually covers values of around ISO 100 or ISO 200 to ISO 6400, with some cameras going a bit higher. This range includes the settings at which the camera produces images that the manufacturer considers to be of sufficient quality for them to be used on a daytoday basis. The level of noise will get higher as sensitivity increases, but the camera’s maker considers it to be with acceptable boundaries. The expansion settings, which can only usually be used once the option has been selected via the menu, push the camera’s sensitivity range a little higher ans sometimes a bit lower. However, the image quality doesn’t meet the manufacturer’s normal standards. These settings can be a useful option, but they are often best kept for emergencies when getting an image is more important than its quality. It’s a good idea to investigate the quality of image that your camera produces at high sensitivity settings before you need to use them in anger. This will enable you to determine how high they can be pushed and at what point you should decide that it’s too dark and you need to stop shooting. Crazy as it sounds, some photographers make the mistake of experimenting with high sensitivity settings in much brighter conditions than they would actually be needed. This gives a false impression of a camera’s performance as noise is usually much better controlled in good light. Low light and shadows give cameras much more of a challenge. So make sure you investigate your camera’s performance in the type of conditions in which you would actually need to use the uppermost ISO settings.

The lowest values are best, right?

If you’re shooting a motionless subject and there’s plenty of light, or the camera is firmly fixed on a tripod, a low sensitivity setting will produce the best image quality. However, using a low expansion setting such as ISO 50 or ISO 32 will often produce a worse quality image than using the base sensitivity setting. Detail levels are often about the same, but dynamic range can be adversely affected and noise levels are likely to be slightly higher. These low values are provided to allow slightly longer shutter speeds or wider apertures to be used in some situations. They may not produce the best technical quality, but they could help you produce a more attractive image.

Shooting in low lighting

Low light conditions are the natural environment for high sensitivity settings. If you’re handholding a camera, a high setting may allow you to use a shutter speed that avoids camerashake from creating blur. As a rule a bit of noise is preferable to blur. Even if the camera is mounted on a tripod, you may need to push sensitivity up a little to avoid incredibly long exposure time when light levels fall.

Using a long lens

Because camerashake is accentuated by long telephoto lenses, they need to be used with a faster shutter speed than you would use if you were shooting with a wide-angle optic. A good rule of thumb is to use a shutter speed that at least 1 second divided by the effective focal length. This won’t be a problem a the height of summer, but in the duller days of winter you may find that you have push the ISO settings up a little to get perfectly sharp results.

Dealing with noise